We often think of the samosa as just a simple street snack, but it actually has a royal history and global reputation. Once a treat fit for kings and nobles, the samosa has transformed into a snack that everyone loves, whether it’s picked up from a bustling street stall in India or served at a fancy restaurant abroad. So how did this once-exclusive dish, filled with rich spices and flavours, become something you can easily buy at your local sweet shop? Let’s explore the fascinating journey of the samosa across time and continents.

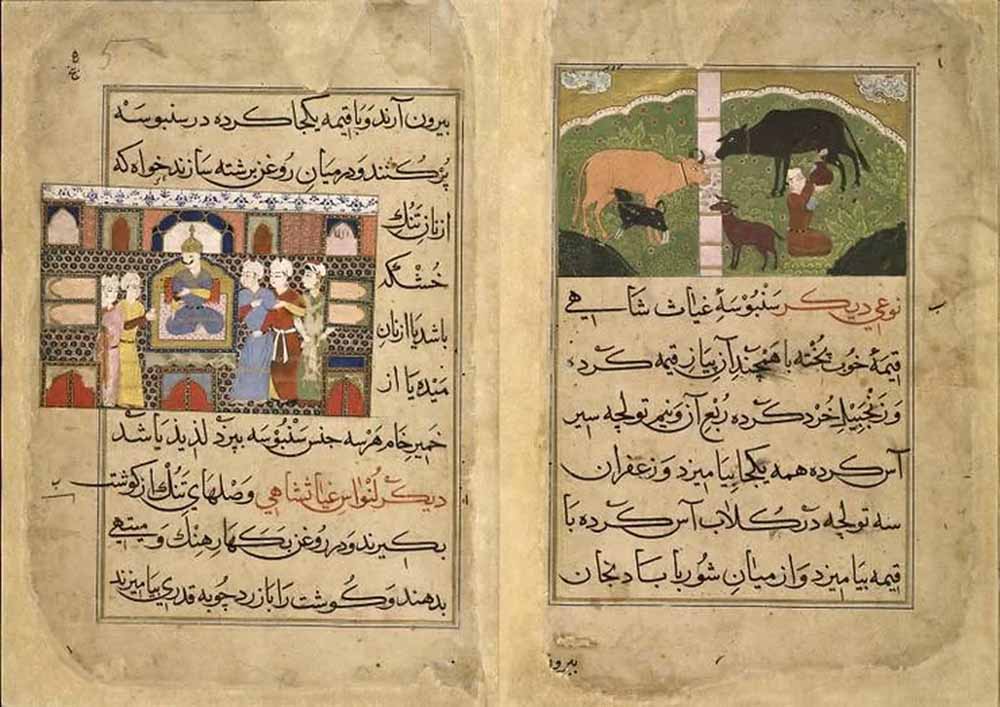

Despite what many believe, the samosa didn’t actually start in South Asia. Its roots stretch back to Central Asia and the Middle East. Arab cookbooks from the 10th to 13th centuries talk about a pastry called 'sanbusak,' which comes from the Persian word 'sanbosag.'

Originally called 'samsa,' this triangular snack, supposedly inspired by the pyramids of Central Asia, travelled across regions, picking up different names along the way. From Egypt to Libya and across Central Asia to India, it became known by variations like sanbusak, sanbusaq, and sanbusaj—all tracing back to Persian origins.

For over 800 years, the samosa has been a favourite in South Asian cuisine, crossing social boundaries. It’s been served at royal feasts for sultans and emperors and sold by street vendors in the crowded lanes of India and Pakistan. No matter where you’re from or what your status is, everyone loves a good samosa.

In Central Asia, samosas were especially popular with travellers because they were easy to make and carry on long journeys. In fact, one of the earliest mentions of the samosa comes from an 11th-century historian, Abul-Fazl Beyhaqi, who described 'sambosas' as bite-sized snacks perfect for people on the go.

The samosa likely made its way to South Asia during the Delhi Sultanate when chefs from the Middle East and Central Asia were brought in to cook for the royal kitchens. By the 14th century, the famous poet Amir Khusro noted that the elite loved samosas filled with meat, ghee, and onions.

Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta also wrote about the samosa during the reign of Mohammad bin Tughlaq in Delhi. He described a delicate pastry filled with minced meat and peas, served at royal banquets. A variation of this, called ’lukhmi’ is still popular in Hyderabad today.

Fast forward to modern South Asia, and you’ll find creative takes on the classic samosa, like Samosa Chaat, where the pastry is topped with yoghurt, tamarind chutney, onions, and spices for an explosion of flavours.

Beyond South Asia, the samosa has evolved to suit local tastes. In Mediterranean Arab countries, the semi-circular 'sambusak' is filled with minced meat, chicken, or cheese, often with onions and spinach. In the Maldives, they have ‘bajiyaa’, usually stuffed with tuna and onions, while in Indonesia, samosas are filled with potato, cheese, or noodles and served with sambal.

In Central Asia, the 'somsa' is baked rather than fried and typically stuffed with minced lamb and onions, though versions with cheese, beef, and pumpkin are also common. And in the Horn of Africa, 'sambusa' is a popular snack in Ethiopia, Somalia, and Eritrea, especially during festivals like Ramadan and Christmas.

These days, the samosa’s popularity spans the globe. Its appeal lies in its adaptability—the fillings change from place to place, but the joy of biting into a hot, crispy pastry remains the same. Whether enjoyed as street food or served up at fancy events, the samosa continues to win over food lovers everywhere.

(Image Credit: baytalfann.com, myfoodstory.com)