There are many women icons we revere for their contributions to the Indian freedom struggle, from Sarojini Naidu and Lakshmi Sehgal to Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi. But have you noticed how these icons are only a handful compared to the many men we rightfully credit for our independence? The many censuses of India conducted by the British Indian government prove that there were millions of women in India during the entirety of the freedom struggle.

What’s more, we know for a fact that thousands of these women participated in the movements against the British government throughout the early and mid-20th Century, especially during the Swadeshi and Non-Cooperation movement, the Civil Disobedience movement, and even the Quit India movement. So why is it that we know very little of the legacy left behind by the women who fought for our freedom?

It’s time we right this wrong by sharing the stories of the women who did participate in, contribute to and make sacrifices for our freedom. Here’s what you should know about the women who joined the freedom movement through some of the toughest times in the early 20th century, when the idea of Indian nationalism and the direction of the freedom struggle were still in their nascent phases.

Making of Indian nationalism and movements

Many consider the period between 1858-1859 and 1905 as one where Indian nationalism was slowly emerging as an idea—an idea which shaped the movements that were to follow in the 20th Century. Even though the Revolt of 1857 was ruthlessly quelled by the British, the idea that foreign rule was doing more harm than good was gradually solidifying. Add to this the economic degradation of Indian traders, manufacturers and artisans, and the many famines that affected the subcontinent—the ones between 1876-1878 and 1886 being the most brutal of all—and the spirit of India was simmering to a point where many were already up in arms, saying enough was enough.

While revolutionary movements and groups were still forming, the most momentous progress made in this direction was the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885. The early INC leaders, however, were mostly moderates until Bal Gangadhar Tilak first made the clarion call for Swaraj or self-rule. But what spurred this change in sentiments was the Bengal Partition of 1905 by the controversial Viceroy, Lord Curzon. Before the Bengal Partition, Bengal was as large as France, and consisted on the present-day states of Bihar, Odisha, Chhatisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam—apart from the entirety of Bangladesh. The announcement that this large state would be divided, that too on the grounds of religion, was enough to make Indians get up and lead mass protests across the country.

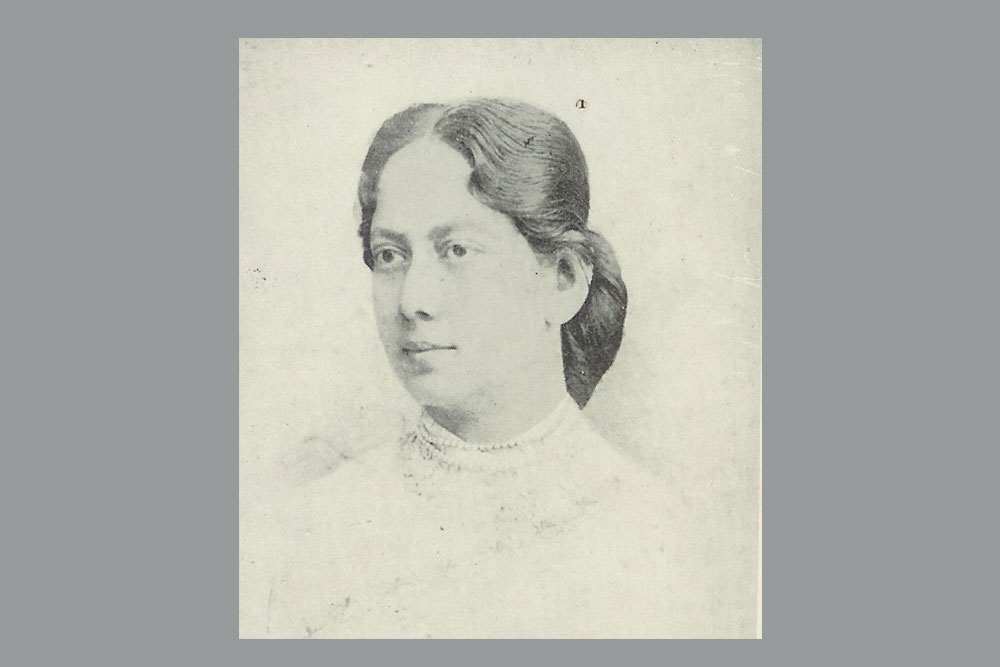

Kadambini Ganguly was one among the many women who actively protested the Bengal Partition of 1905.

Women against Bengal Partition, 1905

Women’s participation in the movement against the Bengal Partition was high and immediate. When Rabindranath Tagore called for Rakhi Bandhan festivals to represent the unity of the people of Bengal, women across regional and religious divides answered his call en masse. Ramendra Sundar Tribedi called for Arandhan Day to be observed on 16th October, 1905—a day when all women would show their protest by not cooking and stepping out to participate in an exclusive women’s protest. This day was equally observed across the length and breadth of the region. Women not only participated in protests, but also attended mobilisation sessions by politicians. Kadambini Ganguly—one of the first women graduates of India—and Swarnakumari Devi (one of India’s first female novelists and Rabindranath Tagore’s sister) attended the INC’s session held in Calcutta, which was to decide on the course of action against the Partition.

Swarnakumari Devi was one of the women who led protests against the Bengal Partition of 1905, and a proponent of Swadeshi.

Pens against Partition

One of the most empowering ways in which women showed their protest was by wielding pens, and publishing their thoughts on essential nationalist themes like freedom, unity in diversity, Swaraj and Swadeshi. Women-run papers and magazines—yes, there were many of those by 1905—not only helped spread awareness about nationalism in English, but also regional languages. Kumudini Mitra, who edited Suprobhat, and Banalata Devi, who edited Antapur, regularly published articles in support of Indian nationalists, freedom fighters, against British propaganda, and even printed advertisements promoting ‘Swadeshi Shilpa’ or indigenous industries.

Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, the eminent women’s rights activist of the time, wrote an inspiring play promoting nationalism, which was published in Bharati. Khairunnesa Khatun, the principal of Sirajgunj Hossainpur Girls’ High School (now in Bangladesh), published an article titled For The Love Of The Motherland, in the magazine Nabanoor. In this article, she urged Bengali women across all religions to support nationalism by promoting Swadeshi, and reminded them that they had an “equal right to participate in these matters”, and had the “responsibility to try to do as much as we can”.

Sarala Devi Chaudhurani was one of the earliest activists who worked to promote Swadeshi handicrafts and products.

Swadeshi women for nationalism

As you can tell, the seeds of adopting Swadeshi goods and boycotting foreign products were sown by the women of India in the early years of the 20th century. While it’s true that Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s call for Swadeshi in 1921 is celebrated as the beginning of a nationalist movement on a larger scale, it cannot be denied that women had already adopted this simple yet powerful means of protest years earlier.

In fact, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani had established Lakshmi Bhandar, a store in Calcutta which popularized native handicrafts produced by Indian women, in 1904—even before the Bengal Partition! Similarly, Khairunnesa Khatun is known to have walked from village to village, promoting Swadeshi among women living in Bengal’s villages. Swadeshi Samitis (or committees) run by women were constantly coming up, and indeed, provided the base for Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement in the 1920s. With the Gandhian Swadeshi movement, women across India came to the forefront, with millions boycotting British-made goods and promoting Khadi as well as other Indian weaves. The stories of women giving up their gold ornaments to fund the nationalist movement during the 1920s is popular enough to stay in all of our minds.

The making of an Indian suffragette movement

The rise of nationalism after 1905 also led to an equal and immediate rise of Indian women’s consciousness. These women were increasingly becoming aware of the crucial role they played in the making of a nation, and were slowly learning to spread their wings. One aspect that is often forgotten about this stage is the emergence of the Indian suffragette movement. Just like in the rest of the world, Indian women weren’t given the right to vote on a platter, but had to protest, mobilise and fight for it.

In this case, women leaders of the British suffragette movement came out to support the rights of their Indian sisters by constantly petitioning the India Office and the Joint Select Committee of the House of Lords and Commons (a deciding body of the British Parliament). While women in Britain got limited voting rights in 1918, the Government of India Act of 1919 allowed the Provincial Councils of India to decide if their women constituents could vote or not. Indian women lapped up this opportunity immediately. Beginning in 1919 in Madras, followed by all British Provinces and Princely States between 1919 and 1929, Indian women not only got the right to vote but also to contest elections in some cases.