The World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report 2017 mentions that, currently “female talent remains one of the most under-utilised business resources”. One of the key reasons why this is so, is partially due to many traditionally held notions about women’s abilities, roles and potential. The finance industry, in particular, has maintained its “all-boys club” image consistently for centuries because of these pre-conceived ideas about women.

The emergence of women leaders in the finance sector, from Ana Botin to Gita Gopinath, in recent decades clearly shows that women are breaking these barriers and progressively, and successfully, making their mark in this industry. But, are they the first of their kind?

Global history, even a closer study of Indian history, shows that while women achievers in finance are getting more (and much-deserved) attention only over the last few decades, they have been significantly contributing to the world of investment, trade and business over the centuries. In most cases, this foray into finance has been from the shadows, even when the woman in question belonged to a royal family.

These exceptional women, no matter which part of the world or times they belonged to, also had severe restrictions while operating their trade or business – which is why they often depended on a complex and close coterie of male servants, agents and confidantes to actually conduct their day-to-day affairs. Let’s take a look at women in finance who must be celebrated for their pioneering efforts during times when gender equality and financial independence were not even on the table.

Women with money power in ancient times

Where there is trade, there are financiers. So, does a closer look at ancient civilisations that thrived on trade bring any women in finance to our attention? It sure does in many parts of the world, including ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Women in ancient Egypt could not only own property, but could also engage in trade contracts in their own name. Evidence from the Old Kingdom shows that women played a huge role in everyday Egyptian economy, even as merchants and vendors in markets.

Recently uncovered evidence from Mesopotamia around 1870 BC indicates that there was a thriving community of businesswomen, bankers and investors among the Assyrians. Financial records preserved on clay tablets in cuneiform script from this period prove that not only did women engage in finance, but also gathered evidence of and reported fraud cases – as shown in tablets written by a woman called Ahaha whose profits were embezzled by (she suspected) one of her brothers. Letters, contracts and even court rulings from this era show that Assyrian women were strong, financially independent and knew how to make their voices heard.

Compared to the Assyrians and Egyptians, women in India seem to be behind the times in the ancient period as law provided them very little avenues for owning property, let alone engaging in trade and commerce. Historian Sukumari Bhattacharji explains in a research article published in the Economic and Political Weekly that both married and unmarried women had the right to own stridhan provided to them by their fathers, brothers, husbands or sons. Whether they could dispose of this “woman’s wealth” on their own is unclear, yet highly unlikely.

Beyond the purdah: Mughal women in finance

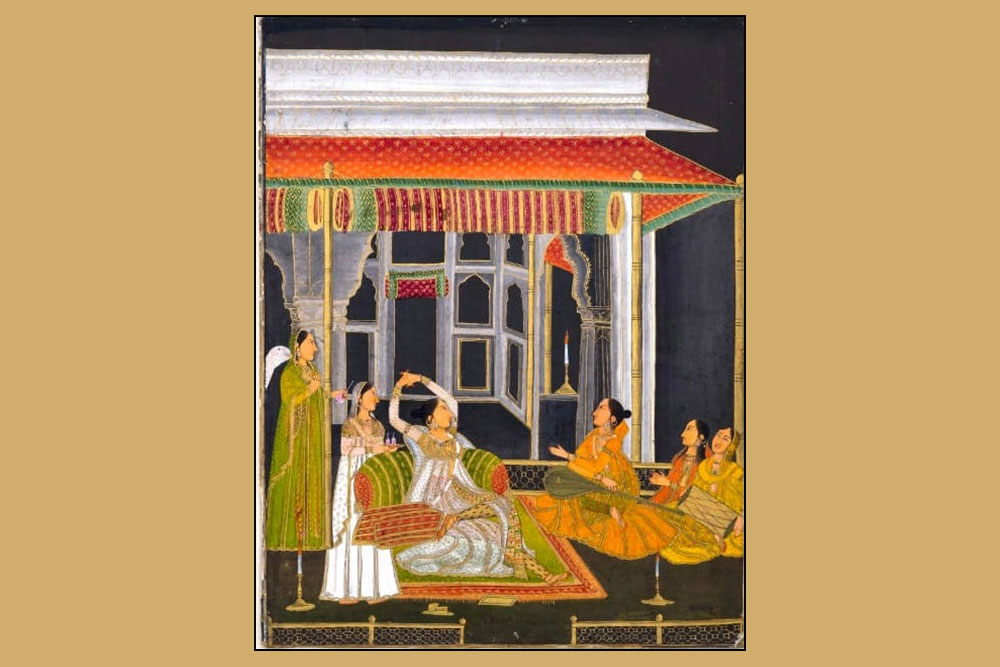

Many might think of medieval India as the “dark ages”, but historical evidence shows that even through the most tumultuous of times, Indian women could control their worldly possessions and even participate in emerging global trade systems—albeit not openly—by stepping out of their zenanas. This is especially true for the Mughal period, where many women in finance made their presence felt. A prime example is queen mother Maryam-uz-Zamani, a Kachhwaha princess from the Rajput kingdom of Amber who married Emperor Akbar in 1562.

The precise extent of Maryam-uz-Zamani’s financial power was felt in 1613, during the reign of her son Jahangir. Portuguese pirates captured the merchant ship Rahimi, which was then the largest ship on the highly profitable trade route from the Red Sea to Surat. Rahimi, and every tradeable good including the invaluable indigo on this 1000-tonne ship, was owned by Maryam-uz-Zamani. The hue-and-cry raised by Jahangir’s court and the Mughal displeasure with Portuguese traders is evident in the records from this period, proving that the queen mother was a very powerful woman in finance.

Maryam-uz-Zamani was not the exception, but one in a long line of Mughal women in finance. Her daughter-in-law and Jahangir’s wife, Nur Jahan, financed indigo and embroidered cotton cloth trade, and also collected trade duties on goods transported from Bengal and Bhutan. Jahanara Begum, who was the eldest child of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal, was given control of revenues from the most lucrative port of the country of the time, Surat. She is known to have more access to liquid cash than any Mughal woman, with her earnings from Surat estimated to be Rs 7.5 lakh per annum according to contemporary reports. Historian Aparna Kapadia estimates that Jahanara’s actual earnings were far greater since she invested in profitable serais (rest houses) and markets in Delhi too.

Colonial pains and the modern Indian woman

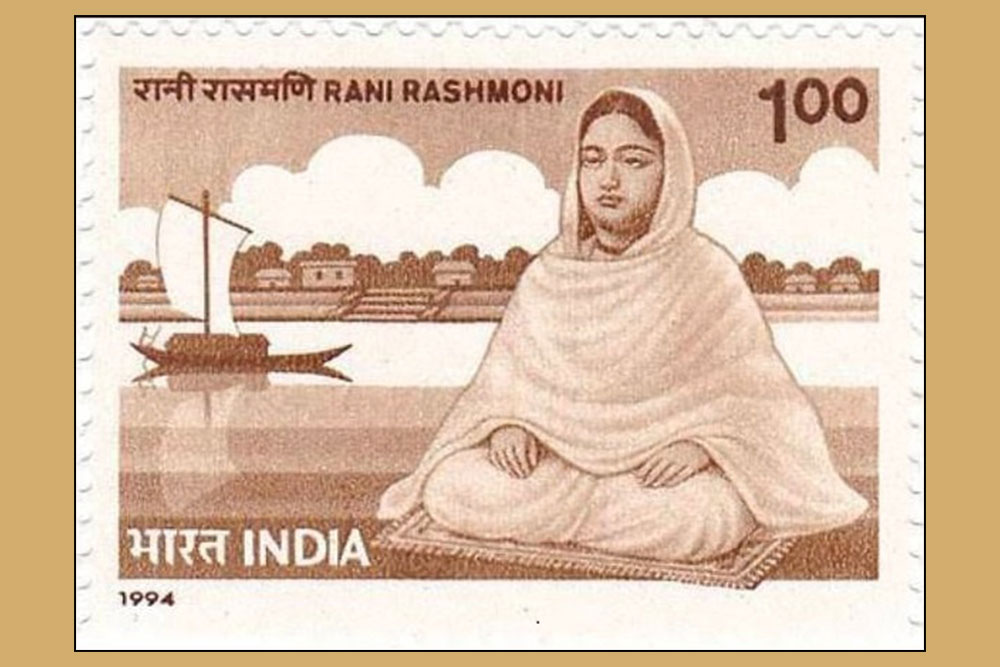

With the economic landscape of India shifting immensely (and definitely not in favour of Indians), you would be hard-pressed to find influential women in finance during the 18th and 19th centuries. This is especially true for upper-caste women, and those belonging to traditional or zamindari families, which tended to look at women venturing out of homes to engage in financial activities as a sign of economic desperation and poverty. The two exceptions of these times were Paikabai Khobragade and Rani Rashmomi, both belonging to the mid-19th century. The former was an entrepreneur who went from being a fruit seller to Vidarbha region’s leading businesswoman through her career spanning decades. Paikabai was also a social activist and is now celebrated as an early Dalit icon and feminist. When it comes to the latter, it suffices to say that the landscape of modern Calcutta was shaped by this pioneering woman in finance. After all, Rani Rashmoni was the celebrated founder of Dakshineswar Temple.

Glimpse beyond Rani Rashmoni’s charitable works and you’ll find a gritty and powerful woman in finance. Born in 1793, this iconic woman was married to a wealthy zamindar, Rajchandra Das, who did not believe that a woman’s only place in the world is at home. He involved her in all aspects of his business, and the couple soon emerged as the leading moneylenders and investors of Bengal. When her husband died in 1830, Rani Rashmoni took over the business and made it work like never before. She not only invested in regional trade and commerce but also in the ventures of contemporary industrialist, Dwarkanath Tagore.

The 20th century clearly improved the financial status of women, slowly but steadily. With better opportunities for education and work, and the need for gender parity in all fields gradually becoming glaringly essential, women were able to get better roles in the finance industry and finally make a mark in the 21st century. This brief history does show that it has taken women in finance centuries of subversion, negotiation and painstaking hard work against all odds to get where they are today. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was the emergence of the modern woman in finance.