When you think of the date August 15, 1947, today, it inevitably brings up feelings of nationalist pride, patriotism, and the need to celebrate the lives of the people who helped us gain our independence. But, underneath it all, most of us do have to acknowledge the fact that our freedom was hard won, and the transition to independent India a difficult one. Giving birth is a messy affair, so how can the birth of a nation be anything but?

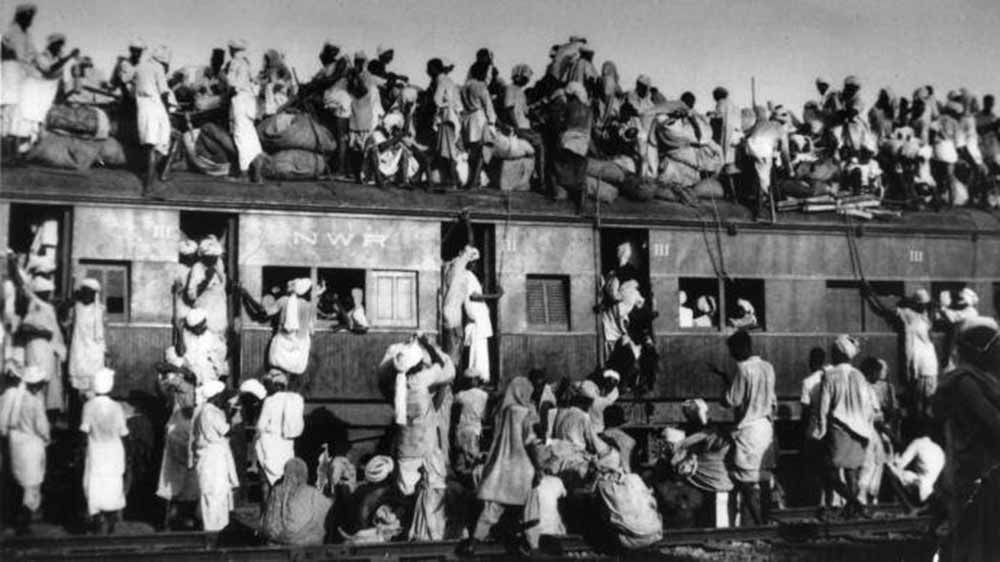

In 1947-1948, as the nations of India and Pakistan were born, millions of its people were displaced during what we call the Partition. United, pre-independence India was divided largely on the lines of religion, which led to the mass exodus of people: of Muslims from India to Pakistan and East Pakistan (now, Bangladesh), and of Hindus and Sikhs from the latter regions to India. People took any means of transport available, or walked, across the newly made borders, leaving homes, possessions, and even loved ones behind.

Historians who have spent decades studying and writing about the Partition, like Urvashi Butalia, Ayesha Jalal, Joya Chatterji, and Gyanendra Pandey, and activists who worked for repatriation and rehabilitation, like Anis Kidwai, all admit that the horror and trauma of this event was immense—even for those who perpetuated it. How can a man who murdered all the 17 women and children in his family, like Mangal Singh (one of the people Butalia interviewed for her book, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India) and his brothers did, survive with anything but immense trauma? How can men, across all religions, truly justify the abductions, rapes, and killings of thousands and thousands of women in the name of honour, shame, and revenge?

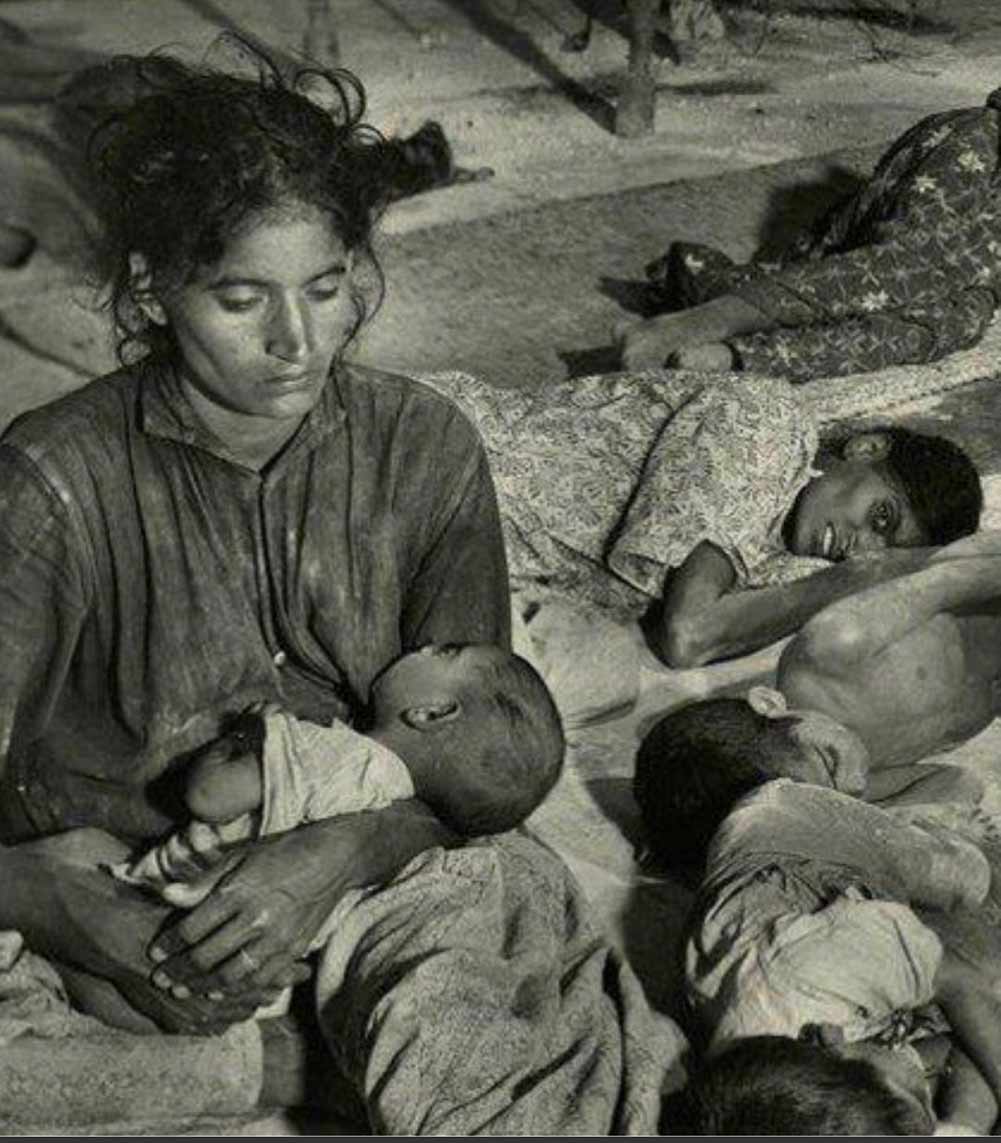

Quite like the Holocaust, the Indian Partition of 1947 was an ethnic genocide, but without any clear black and white. Members of each religion held those of the others responsible, leaders of each nation did the same with the other. And the worst of this entire event was endured by women of the subcontinent, no matter what their religion. Here is a brief, yet vital exploration of what women went through during and after Partition.

Sawing Through A Woman: Depictions Of Partition

The notion of Bharat Mata, the anthropomorphised depiction of the land mass that was the Indian subcontinent, may have first been brought up by Aurobindo Ghosh, but this sort of depiction soon found popularity among the masses too. This was especially true for the Hindu masses, who saw Bharat Mata as not just a mother, but a goddess. This portrayal of India as a mother figure was also used to depict what had happened during Partition.

A brilliant example of this is a cartoon published in 1947, titled Sawing Through A Woman. The cartoon depicted a woman in a large box (her mouth covered, indicating the lack of agency both the nation and its women faced during Partition), with Nehru and Jinnah cutting the box apart with a saw, while Gandhi watches on, and a British officer hopes everything goes right for her. A chilling visual indeed, given how Partition was played out over the bodies of both the nation and its women, and the extremely gendered violence they experienced.

Women As Wealth: A Look At Honour And Shame

In her 2016 article, titled Violence Against Women During The Partition of India: Interpreting Women And Their Bodies In The Context of Ethnic Genocide, historian Arunima Dey describes the two kinds of gender-based violence women endured during Partition:

1. Violence inflicted by men of the opposite religion, usually involving kidnapping, rape, forced marriage or conversion, genital mutilation, and public humiliation. This kind of violence was inflicted to abase the “honour” of the men of the rival religion.

2. Violence inflicted on women by their own family members, usually men, but often with the complicity of women too. This kind of violence included honour killings as well as women being pushed to commit suicide in order to safeguard the purity of the community and the honour of the family.

Dey insists that no matter which kind of violence was inflicted on women, the fact remains that during and after Partition, these “women were not treated as humans but as markers of communal and national pride.”

This argument, also supported by every other historian of Partition, is clearly one that endures even today, unfortunately. The ideas of honour and shame are so intrinsically linked to the bodies—or rather the chastity, virginity, or purity—of women, that even women themselves tend to believe in them within the parameters of patriarchal society. Call it a pillar of patriarchy, or simply a means of treating women as subhuman, the idea of honour was clearly used during Partition by men from all sides. And the damage was long lasting.

Several estimates reveal that between 75,000 and 100,000 women were abducted and raped during Partition. Despite the Delhi Pact of 1950, also known as the Nehru-Liaquat Pact based on the Prime Ministers who signed it, and Central Recovery Offices being set up across both nations, many of the abducted or converted women were never recovered. Some, as the historians show, didn’t even want to be discovered and returned for the fear of facing dishonour and rejection on their return.

Trauma, Betrayal And The Legacy Of Partition

Putting yourself in the shoes of these women is impossible, and even the historians who do it live with the trauma of it. In a 2016 interview, Butalia explained how interviewing people who lived through Partition was “very unnerving and very burdensome”, and how she used to cry while reading the transcripts. It’s also important to note here that Butalia’s family shifted to India from Lahore during Partition, so she probably had stories that brought the event even closer home. One that she shares in the same interview is about her maternal grandmother, who was left behind in Pakistan. Butalia believes she must have endured immense psychological trauma, waking up one day to find that all her children and grandchildren had left her.

But this is not the only kind of betrayal women who survived the Partition must have felt. Many women who were abducted and forced into marriages not only developed Stockholm Syndrome, but also took to their new lives in silence. Kidwai, in her book titled In Freedom’s Shade, explains how many women she talked to did not want to leave these relationships for the fear of facing a second displacement, and another round of forced marriages to “recover” their honour. On the other hand, were Partition stories of people like Zainab and Buta Singh.

Zainab was abducted from her family while travelling to Pakistan, passed from man to man, until Buta Singh, a Sikh ex-soldier in the British Army, bought her and married her. It is believed the couple fell in love, and had children. In the wake of the Nehru-Liaquat Pact, Zainab was discovered and deported to Pakistan. Buta Singh went to visit her in Pakistan on a short-term visa (or illegally, the stories differ), but was arrested. Zainab has to appear at his trial, where it was revealed that she had married again. Surrounded by male relatives, she denounced Buta Singh and claimed she felt no love for him. Buta Singh, the legend goes, committed suicide by jumping on the train tracks of Shahdara station in Pakistan.

While it’s simply impossible to recount the stories of Partition in this brief account, it’s quite clear that while women faced the queen’s share of the violence, the trauma was shared by all. Since familial honour and shame is associated with what happened to the women during Partition, many voices and stories remain unheard—often because the perpetrators know what they did was wrong, and chose to live in silence with the consequences of the horrors they bestowed rather than “be caught”.

So, while our independence is something we absolutely should celebrate, the legacy of Partition should not be forgotten or relegated to the shadows of history out of a sense of shame or misplaced honour in women’s bodies. The fact that the women of this nation have endured unspeakable horrors and generational trauma to survive, and live a life of freedom won at a great price, should, instead, inspire us to hold a mirror up to past actions, and swear and strive to do better.