Every human being has a right to education, and every child deserves to go to school to get a good start in life. While we all may know this to be right, the fact remains that women and girls around the world face many obstacles on the way to getting an education. The United Nations observes that just the primary education system in India suffers from a huge gender gap, largely due to poor infrastructure, dearth of teachers, lack of hygiene and access to bathrooms (especially after girls start menstruating) are a few of the problems that hinder girls from getting school education today.

If you just look at the last Indian Census report from 2011, the magnitude of this gender gap becomes apparent. The total literacy rate of the country stands at 74 per cent, with the rate of literacy among women at 65.46 per cent. Although the new census report for 2021 hasn't been released yet, the National Statistical Office reports that the total literacy rate of the country in 2021 stands at 77.7 per cent, with total female literacy at 70.3 per cent. Quite far away from being literate, let alone educated, aren’t we?

But hope is not quite lost, especially if you take into account the journey women’s education in India has made so far. The Census reveals that the female literacy was at 54.16 per cent in 2001, which may not make the 2011 statistics seem like a huge improvement. But compared to the fact that female literacy was at a meagre 8.86 per cent in 1951, when the first Census after independence was completed, we really have come far.

Educating girls during colonial times

What makes this journey even more remarkable is the fact that female literacy, or the prospect of attending school, let alone college, was nil around 200 years ago. The 1820s in India were a far cry from today’s world. The popular belief among Indians across religious and regional boundaries was that educating girls would undermine their feminine qualities and bring disgrace to the family since the right place for women was thought to be within homes. Further, women at that time had little or no legal rights to property, or even their lives, as proved by the existence of barbaric practices like Sati or widow burning. Child marriage was another problem plaguing India, and hindered even the idea of education for the girl child.

Christian missionaries were the first to be allowed to operate schools for both men and women as per the Charter Act of 1813. Robert May of the London Missionary Society was the first person to open a school exclusively for girls in the region of Chinsurah, Bengal, in 1818. After this pioneering act, many other missionary schools for girls were started across the country. Notable among them were Mary Ann Cooke’s school under the Church Missionary Society in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, and Cynthia Farrar’s American missionary school in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra. Despite these efforts, enrolment at these schools was never high, and the girls who were sent to study there usually belonged to the depressed classes or those who belonged to families that had converted to Christianity.

The first school for girls, by Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule

It is within this context that you must see the efforts put in by reformers like Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule. Savitribai, who is credited to be the first female teacher of India, was herself illiterate when she married Jyotirao at the age of nine years. Jyotirao taught her how to read and write himself, and then sent her to Cynthia Farrar’s school in Ahmednagar for further training. This was also where Savitribai bonded with Fatima Sheikh, who is believed to be one of the first female Muslim teachers of India. Both women finished their training at the missionary school in 1847, and then laid out their plans for the first Indian school for girls with Jyotirao.

The Phules opened the first girls’ school in August 1848, in the house of Tatyasaheb Bhide (or Bhidewada) in Pune. Both Savitribai and Fatima Sheikh were teachers at this school. Although the school had nine girls from various social backgrounds, including Dalit and Muslim families in Pune, the opening of the school itself caused quite a furore. After all, the mindset of the time was dead-set against women’s education, especially when imparted by teachers belonging to the Dalit community. But the Phules’ plan was to help Dalits, women and those of other marginalised communities, get emancipation through education, so they remained undeterred in their efforts. They opened 18 more girls’ schools in and around Pune between 1848 and 1852, and even opened night schools by 1855 to ensure that those who had to work during the day had access to education.

Bethune’s school for girls in Bengal

While the Phules were solidifying and popularising their girls’ schools in Pune, Bengal was witnessing a renaissance in the 1830s and 1840s that would make such schools popular across Bengal. Leaders of the movement, like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Dakshina Ranjan Mukherjee, Ramgopal Ghosh, and Madan Mohan Tarkalankar, all stood up to the patriarchal views held by Hindu society at the time to promote women’s right to education. They delved into the Hindu shastras to argue with elite Brahmins that women had been provided with education since ancient times, and keeping them in the darkness of homes would hinder the progress of society as a whole.

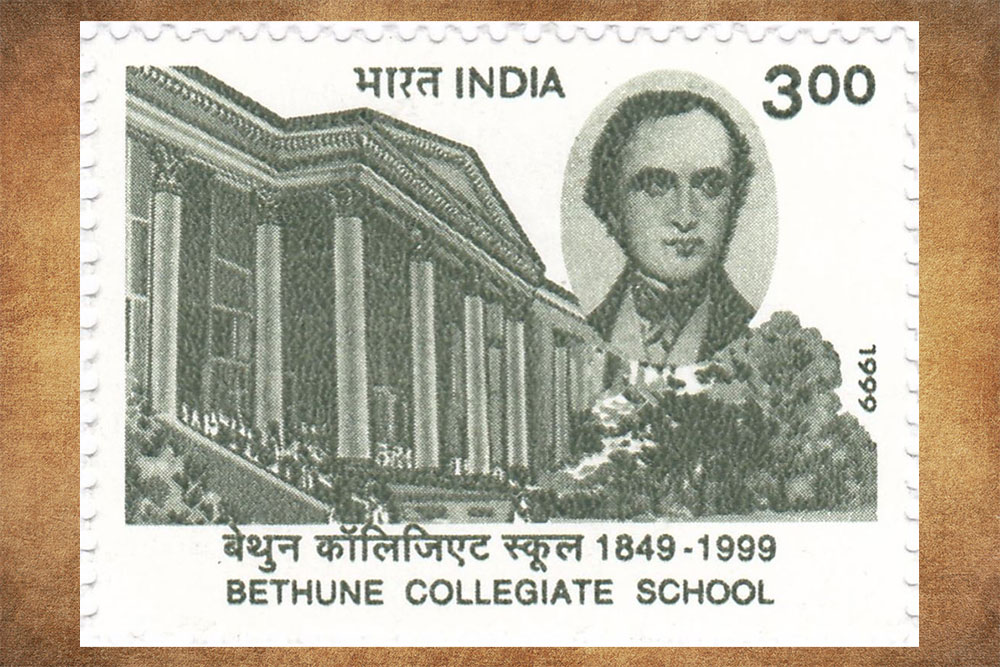

Enter John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune, a Cambridge-educated lawyer appointed to the then Governor-General’s Council in Calcutta. Bethune and the four aforementioned Indian reformers, helped found the Hindu Female School of Calcutta in 1849 in Mukherjee’s home in Baitakkhana (now known as Bowbazar). Mukherjee donated a piece of land he owned in Mirzapur later, where a proper school was built, which was renamed Bethune School. The school started functioning on 7th May 1849 with 21 girls enrolled. Bethune donated all his movable and immovable property to the school, and after his death in 1851, the school was shifted to a new, larger building in Calcutta’s Cornwallis Square.

Vidyasagar, who was appointed the Secretary of the Managing Committee for the school, worked for the rest of his life to make girls’ schools popular across Bengal. He started a fund called Nari Shiksha Bhandar to open more schools for girls. By the end of his life in 1891, Vidyasagar had successfully opened 35 girls’ schools across the region, and enrolled 1,300 girls.

By the end of the 19th century, and through the efforts of Indian social reformers like Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and other leaders of the Bengal renaissance, a case had been made for Indian women’s right to education. Patriarchal values that hindered girls from even dreaming of getting an education had been challenged. And slowly, women were able to not only access school education but also walked into colleges in India and abroad to get higher education. It was a difficult road to traverse, but 200 years down the line, every woman and girl in India must thank the pioneers who helped them start on this journey of education by opening the first girls’ schools of India.