Aspirations, Access & Agency: Women transforming lives with technology, a book by the Reliance Foundation and Observer Research Foundation, tells the stories of Indian women leaders from across the nation who have emerged as agents of technological change and socio-economic inclusion and are using information and communication technologies (ICTs) to help their communities build pathways to better futures. Written by Antara Sengupta, this excerpt shares the story of Kajal & Sajida Khan.

The Mewat district in Haryana has an age-old connection to folklore and poetry. Several historians point out that Mewat’s documented history was sourced from folklores and songs by Sufis (Muslim religious poets) and saints. In present times, Kajal (23) and Sajida Khan (29), two young women from the district, are using this legacy of storytelling to help the community, but with a digital twist.

Kajal and Sajida spend the day visiting at least 15 houses in Punhana and Nagina blocks to showcase a story titled ‘Pyaara Munna’ (adorable child) through a digital storytelling platform on mobiles. The story describes the various symptoms of childhood pneumonia and how it is important to seek treatment at a recognised healthcare centre rather than local village doctors. Since 2019, they have been helping the women of the community by providing them information and connecting them with health centres for maternal and child health, immunisation, family planning, and tuberculosis.

Mewat is currently classified as an ‘aspirational district’ by the Indian government. The aspirational districts programme was launched by the government in January 2018 to accelerate progress and transform the 112 most underdeveloped districts across the country. Like several other underdeveloped districts that are part of this programme, Mewat ranks low in multidimensional poverty indicators, including progress in education, health, and basic infrastructure.

Sajida and Kajal seem to have risen above these odds to help the larger community. They are amongst the 44 percent of women in rural Haryana who have completed 10 or more years of schooling, and are amongst the about 34 percent of women in rural Mewat who are literate. Sajida and Kajal have completed their undergraduate degrees. Additionally, Sajida has finished a general nursing and midwifery (GNM) programme, while Kajal is currently enrolled in one.

Sajida recalls that there were only one or two other girls in her class in school. “In Mewat, when I was in school, girls were not allowed to leave home freely or even study. If not for my father, none of my six sisters would have been educated today,” she says. Sajida’s father, a driver with the local health department, defied the family and community to educate his daughters and even encouraged them to complete their undergraduate degrees.

Kajal, the oldest of four siblings (two sisters and a brother), came from a humble home. Her father is a daily wage labourer and her mother a housewife. Even so, her parents encouraged her to study, “We would help our mother with household chores, but she would insist that we use our free time to study,” she recalls.

Sajida and Kajal’s families were friends, but the girls lost contact once they got married. But they met again in 2019 when both applied for vacancies at ZMQ, a not-for-profit organisation that develops technology-enabled tools to help marginalised communities with information.

While growing up, both girls’ fathers owned basic mobile phones that they were seldom allowed to use. When Kajal started attending college, her father bought her a basic phone so she could keep him updated on her whereabouts. “He wanted to know if I am safe and coming back home in time,” Kajal says. Sajida, on the other hand, could only buy a phone once she was married.

Sajida and Kajal were always bothered by the fact that women’s activities and education were restricted. For instance, women were not allowed by the men of their families to participate in cultural programmes that involved outsiders. While her family was more progressive than others in the community, Sajida had to encounter these restrictive expectations in her marital home. Her husband and in-laws did not want her to work to earn any livelihood and even stopped her from studying further. She even applied to become a school teacher but her father-in-law refused to let her take up the job. But she was determined to use her education to help other women in the community. She even saved INR 100 on her own for the GNM course, and sought help from her father to cover the fee shortfall.

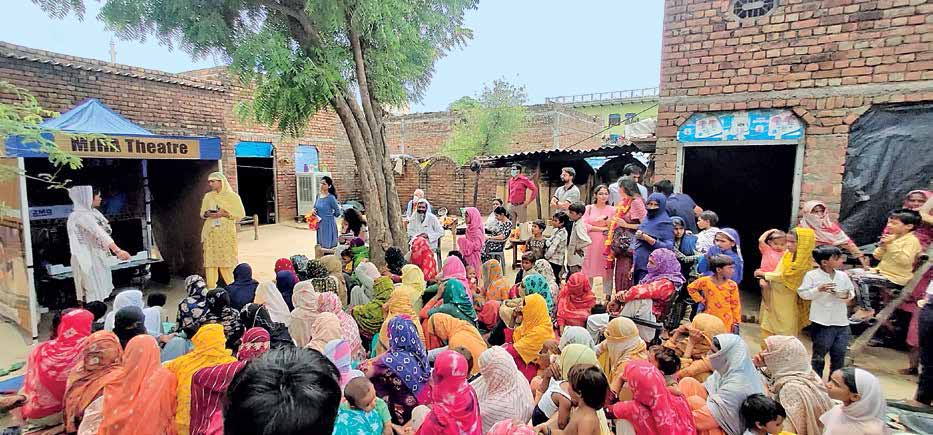

The ZMQ opportunity came as a blessing for both women in 2019. In 2012, ZMQ launched MIRA, an integrated mobile phone tool that provides critical information to pregnant women and enables them to access health services in low-resource settings. Stories on the MIRA channel are produced in the Mewati language and show fictitious characters in situations involving pregnant or new mothers. Young women are engaged as MIRA workers to visit households in the community and disseminate information about women’s health and childcare.

But despite becoming a MIRA worker, things did not get any easier for Sajida. She remembers walking over two kilometres with her infant son while on the field because her in-laws and husband were not supportive of her work. But she was determined to balance both household and fieldwork and continue to work for a cause she believes in. “I made it very clear to my family that I will not stop just because I am a woman,” she says.

As for Kajal, who worked as a school teacher before becoming a MIRA worker, this was an opportunity to encourage other women to learn. “I saw an opportunity to teach more women, while also helping them with useful information,” she says.

Sajida and Kajal were trained by ZMQ officials on various health concerns, including tuberculosis, pneumonia, malnutrition and neonatal care so that they disseminate the correct information and direct women to the appropriate healthcare centres. MIRA workers are also trained to screen high-risk pregnancies and register pregnant women and the newborn babies on the app so they can be monitored and informed about immunisation schedules. The women also receive notifications on the app to make them aware of their healthcare schedules. “The app is connected to the local healthcare centres, so they also have a record the number of pregnant and lactating women and newborns,” explains Kajal.

On the job, Kajal and Sajida inform women about immunisation, and health and nutrition, and show them videos on the MIRA channel to educate them about various healthcare issues and enable access to health services, all using mobile phones and tablets. Both agree that the women they visit listen to them as they feel a sense of connection with them. “I tell them stories about my own home, the struggles that I faced and then also use the stories in the MIRA channel,” Sajida says.

But it is not always easy to convince women who do not believe in immunisation or postnatal healthcare. To handle such situations, Sajida goes beyond her job role to lead by example. She immunised her son in front of a group of women to show them that it was safe. “Some of them became our friends and we also create a social circle this way,” she says. But if even such measures do not work, Sajida and Kajal turn to the community leaders, such as the panchayat or a religious leader, or the men of the family.

Sajida says it was hard to find women in her community who are confident and willing to take up jobs as MIRA workers as societal and familial pressures mean that many women do not take up jobs outside the family business. “We went door to door, met their families and explained to them how the women can balance all the work, and can also earn for the families,” she says. It is only through this that many women can be encouraged to become powerful local role models and inspire others to take on similar roles. But there are many challenges to overcome.

Sajida and Kajal have encouraged at least 10 women to become MIRA workers in the eight months since they joined, and have trained 50 others so far. They try to install the app on the phones of all the women that they come across, and even teach them how to use it. “The women we train are not always digitally literate. We begin with teaching them basic phone functions and then train them on the portal,” Kajal says. Sajida and Kajal also share the stories on the app with Anganwadi workers and ASHA workers, who find it useful when performing their jobs.

To read the inspiring stories of these women revolutionising ICT use across the length and breadth of India, click here.