“I have come to believe in destiny a lot, because, of course, God helps those who help themselves, and I’m a true example of that,” says Deepa Malik, during an exclusive interview. You may know her as India’s most decorated para athlete—she has been awarded the Arjuna Award (2012), Padma Shri (2017), and the Khel Ratna (2019)—but her journey is testament to the fact that this woman and mother of two daughters, has looked some of the most difficult obstacles in the eye with nothing short of sheer will and passion, and come out on top. This Disability Pride Month, we bring you her inspiring story, in her own words.

How motherhood and passion for sports changed her life

Diagnosed with weakness in the lower limbs as a child (she was only five years old), Malik went through everything from surgery to aggressive physiotherapy. “Those four years of my childhood kind of prepared me for what was coming much later in my life.” By the time she recovered her ability to walk at the age of nine, she had discovered that the outdoors were in her DNA. She believes she was fortunate enough to grow up in a time when sports like baseball, kho-kho, hockey, football, kabaddi, and basketball were available to schoolkids, especially in the Kendriya Vidyalayas. She participated in sports like basketball and cricket through her schooling, and after getting married, the outdoors continued to played a huge role in her life.

When Malik’s elder daughter, Devika, was diagnosed with hemiplegia (which leads to paralysis and muscle control problems on one side of the body), it became “a revision from her childhood”. “I just replicated what my parents did for me, for my daughter,” she says. By the time her daughter was recovering, Malik got her tumours back. Surgeries, this time around, led to chest-below paralysis in June 1999. “When that inability to walk came to me, it came to me in motherhood. And this time, I thought this was the best way to be a role model for my daughter,” she explains.

“Sports became a saviour for both of us, and motherhood became easier because I could actually lead with an example,” she says. Her daughter’s education, combined with Malik’s own passion for a fit life, dictated, in a way, the course her life would take. “Disability and sports, together, have only made me a better mother,” she says, adding that her daughters have been her physiotherapists, nurses, gym partners, sports conditioning trainers, and travel companions—all of which helped them become friends and comrades, and bridged the generation gap completely.

Malik’s venture into para sports helped these three women become a team with a common dream, making their bond so much deeper. This is why Malik insists that her inability to walk “became a blessing in disguise. I feel blessed that I’m in the body that I live in,” she adds.

In search of an identity beyond being wheelchair bound

In 1999, Malik’s identity became that of a person who is “wheelchair bound”, and she immediately saw the problem with this identity. “I love wheels. Wheels are nothing but a symbol of movement. It has helped the human civilisation progress. Then why was I being singled out as someone who was sitting it out on wheels?” she asks. Realising that society—which has traditionally translated the disable as people who are unfit, dependent, a burden, or even cursed—was trying to define her persona for her, Malik wanted to break free. That’s when Malik decided to take up para sports.

“The pivot point of any sporting activity was taking care of your body. So, I decided it was better if I go to a stadium, a gym or a swimming pool rather than going to a hospital or physiotherapy centre where I’d be called a patient,” she explains. Her daughter’s research into para sports and meeting with likeminded people shaped her journey further. Though it started late in her life—she became a swimmer at 36 and an athlete at 40—Malik learned the nuances of para sports, and quickly mastered them to become the icon we know her to be. “In the quest of an identity of a happy person instead of a wheelchair bound patient, I ended up being a sportswoman,” she says.

And what a sportswoman she is! Malik is not only the first Indian woman to win the silver medal at the Paralympics (for shot put in the 2016 Rio Olympics), but also holds the record for being the only Indian woman to get three consecutive wins at the Asian Games (2010, 2014, 2018). With numerous national and international medals to her name, she is also the first person in India to get a license for a modified motor rally vehicle, and has participated as a driver and navigator in some of the toughest terrains, including the Raid de Himalaya (the world’s highest rally raid).

Gearing up for the Tokyo Games

Malik isn’t the only para sports star this country has produced in the last 10 years, but she’s clearly one of the most influential as a role model. “In the last decade, para sports have been accepted as mainstream sports. I have been very fortunate to be a continuous part of this change, sometimes even leading from the front,” she says, adding that government sports policies have now become more inclusive, and the approach towards training, nutrition, cash rewards, job opportunities, etc have also become at par with able-bodied athletes. The impact that the emergence of para sports in India has had is clear, especially at international sporting events.

“The moment para sports, in the global arena, brings home medals, it’s an automatic declaration that our country has now become inclusive. The mindset changes. When people see physically challenged heroes performing, and raising up the tricolour in an international arena, it becomes such an inspirational, positive thing that gives hope,” she explains. Right now, Malik’s attention and sole focus is bringing in a huge medal haul from the Tokyo Olympic Games, especially since the Games had to be postponed last year.

Insisting that the Tokyo Games will “declare humanity’s win over the global pandemic”, Malik argues that coming back home with medals will generate a lot of hope and prospects for more changes in the right direction. “It will be a reminder to the entire nation that yes, now para sports has arrived and it’s definitely a medium to bring glory. To the tricolour,” she says. “I really want to see our para heroes get into the textbooks as role models, and it will happen,” she adds.

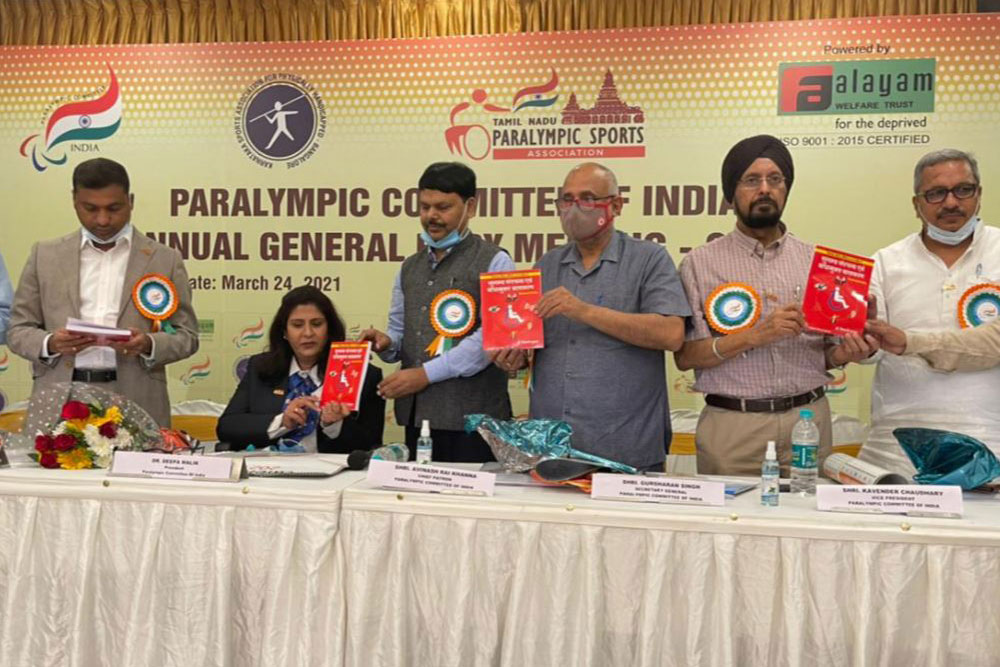

Malik also believes the para athletes selected for the Games this time are indeed going to make the country proud. “This is the first time in history that one of the biggest contingents across many sports is going to go. I’m very proud of the fact that I got to serve the Paralympic Committee of India as its president, which itself is symbolic of an athlete-centric federation,” she says, adding that her Paralympic squad has para athletes in sports like shooting, swimming, canoeing, taekwondo, and archery, apart from athletics. Most of this squad also hold the top-eight ranking in the world, have held world records, and many of them are extremely talented para women athletes.

Her expectations from this squad are high, as she also believes many of them will create new records too. All of this, she believes, will help level the playing field at home for these and other emerging para athletes. So, what are the other aspects which can increase inclusivity? “Infrastructure is the biggest leveller,” she says, “second, is the mindset. Third, is the acceptance of the fact that these are mainstream sports, and not charity sports.”