Ask any girl or boy today, and you’ll find them excited about going to college—not just because of the education and career prospects a college education offers, but for the culture and sense of community. It’s the first time children are out of their uniforms, ideally get to study a subject they enjoy or have a deep interest in, and build meaningful relationships with peers who have made similar life and career choices. No wonder those relationships often last a lifetime.

But while the current generation has the opportunity, nay the privilege, to get some kind of college education today, the same wasn’t true for everyone—especially women—just over a century ago. While the early 1800s saw the emergence of colleges and institutions of higher education for Indian men, Indian women had to fight longer and harder for their right to education. Here are some facts that will put this long struggle in perspective.

The beginning of higher education for Indian women

While the first schools for girls were set up in India beginning in 1818, these were Christian missionary schools and not many girls got to enrol. The prevalent notion at the time was that getting an education would ruin the femininity of women, and they’d leave the homestead and bring dishonour to the family. It was only with the work of social reformers like Jyotirao Phule, Savitribai Phule, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and British reformers like David Hare and John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune that schools for girls were opened in the 1840s and 1850s. Colleges for women emerged even later.

After Bethune’s school for girls became popular, the Bethune College of Calcutta was established in 1879—making it the first institution of higher education for women. In 1875, women were given the chance to enter the Madras Medical College as students, if they got special permission. In 1876, women were allowed to sit for entrance exams at the Calcutta University (but weren’t actually allowed to enrol until 1878), and in 1882, Bombay University was also opened for women students. Despite this, getting women who had been able to finish their schooling and had enrolled in these institutions was difficult, because the focus even then was on a woman’s domestic roles instead of her prospects beyond it.

So, naturally, when the first few women in India graduated from these institutions, it was a very big deal. Here were women who had beaten all sorts of odds in a society that gave them even an inch of their rights only grudgingly. If you can put yourself in the shoes of women living at that point of time, you’d realise that these pioneering Indian women graduates were superheroes in their own right. Here’s what you need to know about these inspiring women.

Kadambini Ganguly

In 1882, Kadambini Ganguly became one of the first two women graduates of India, when she received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the Calcutta University (the convocation was held in 1883). Following her convocation, Ganguly was awarded a government scholarship of ₹20 per month for women medical students enrolled at the Calcutta Medical College. While she wasn’t the first Indian women to get a medical degree, Ganguly later became the first Indian as well as South Asian woman to practice medicine after she graduated from the Calcutta Medical College in 1886. After graduating as a gynaecologist, Ganguly started a successful private practice. Married to Dwarkanath Ganguly, a prominent Brahmo Samaj leader, she was appointed to the Lady Dufferin Women’s Hospital on a salary of ₹300 per month. In 1892, she also travelled to Britain and got further training from Dublin, Glasgow, and Edinburgh. On returning to India, she continued practising at the Women’s hospital until her death in 1923.

Chandramukhi Basu

Graduating alongside Kadambini Ganguly from Calcutta University in 1882, Chandramukhi Basu’s life took a very different trajectory from her classmate’s. Born in a Native Christian (Indians who converted to Christianity during colonial times) family, Basu wasn’t allowed to study in Bethune School for girls, which was reserved for Hindu girls at the time. She attended Reverend Alexander Duff’s Free Church Institution, but had to get a special dispensation in 1876 to be able to sit for the final exams. She then cleared the entrance exam for Calcutta University’s Bachelor of Arts programme, but wasn’t allowed to enrol. It was only after the university passed a special resolution in 1878 that both Basu and Ganguly were allowed to enrol as students together. After graduating, Basu went on to become the first Indian woman to get a Master of Arts degree from Calcutta University in 1884. She then joined the Bethune College as a lecturer in 1886, and in 1888, became its principal and the first female head of an undergraduate academic institution in South Asia. Retiring in 1891, Basu spent her retired life in Dehradun.

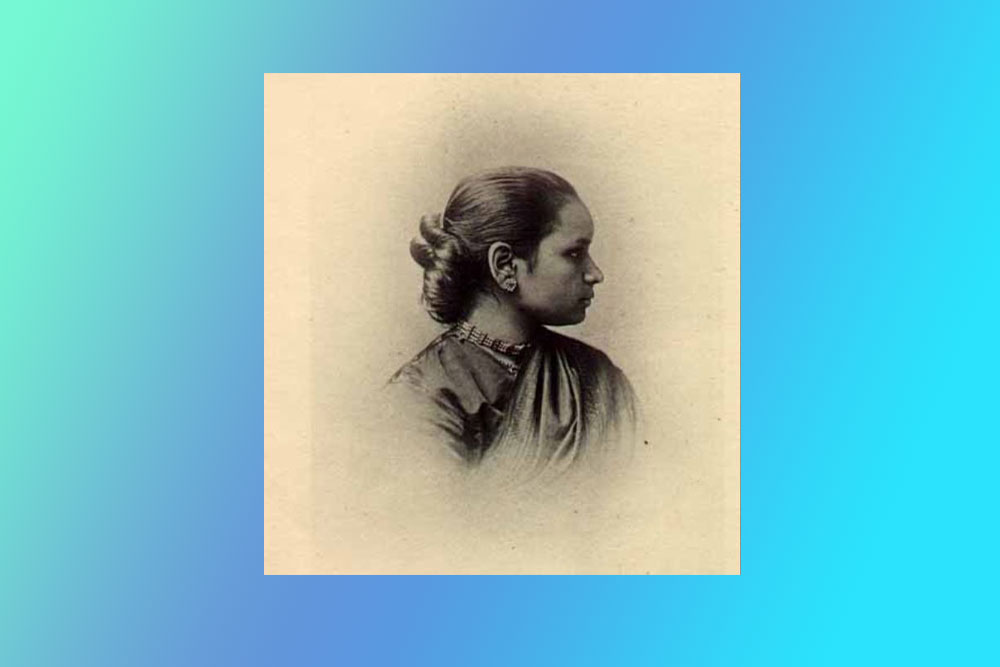

Anandibai Joshi

Anandibai Gopalrao Joshi was the first Indian woman to get a medical degree in 1886, beating Kadambini Ganguly by just a few months. Joshi was born in the Bombay Presidency in 1865, and married to Gopalrao Joshi, who was her senior by 20 years, at the age of nine. When she was just 14 years old, Joshi gave birth to a son who lived a mere 10 days. Feeling that Ayurvedic knowledge and Indian midwifery were not enough to help women face these gynaecological and natal issues, Joshi and her husband shifted to Calcutta to get her enrolled in a missionary school, where she learned English and Sanskrit. Gopalrao then decided to send his wife to the US for further education, with the help of New Jersey-based missionary, Theodocia Carpenter. She enrolled in the medical programme at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania at the age of 19, and graduated with an MD in Obstetrics at the age of 21. Her thesis was titled Obstetrics Among The Aryan Hindoos. On her return to India in late 1886, she was appointed as the physician-in-charge of the women’s ward at the Albert Edward Hospital in the state of Kolhapur. However, Joshi contracted tuberculosis the following year, passing away untimely in 1887 at the age of 22.

Kamini Roy

A junior by three years of Ganguly and Basu, Kamini Roy attended Bethune School and Calcutta University to become the first Indian woman to graduate with honours on completing her Bachelor’s Degree. Roy joined Bethune School in 1883, and although she was considered to be a mathematical prodigy, she chose to study Sanskrit in college. After graduating in 1886, she started teaching Sanskrit at Bethune College, and later retired in 1894 to focus on publishing her works. She married Kedarnath Roy at the age of 30 years, which was controversial at the time. Influenced by Rabindranath Tagore, Roy continued to contribute to literature, and soon emerged as a leading reformer working for women’s rights. She was one of the many women leaders to work for Indian women’s right to vote in 1926. Roy passed away in 1933.

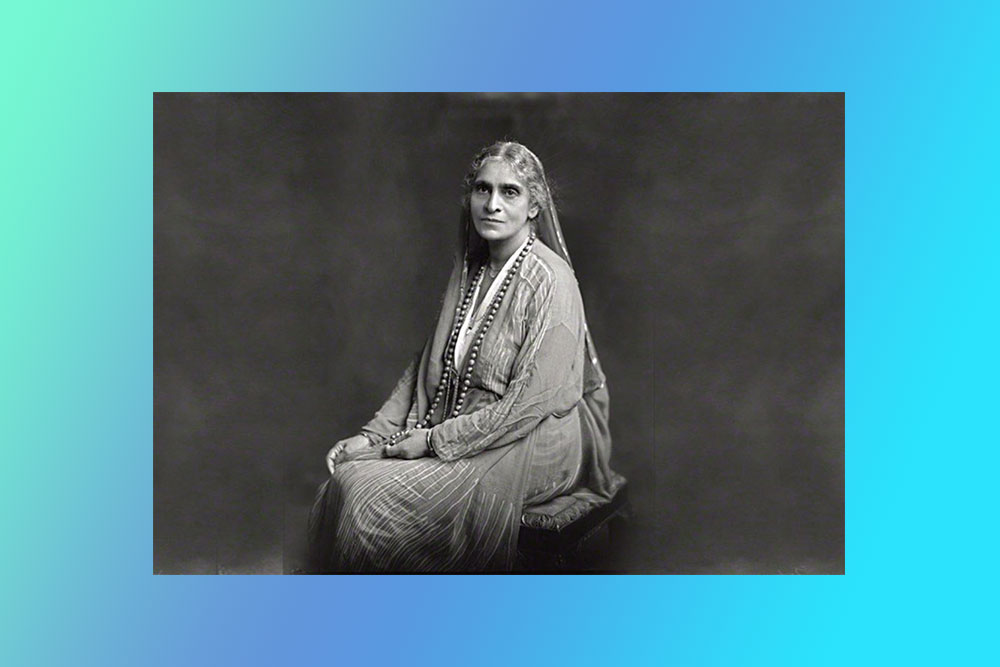

Cornelia Sorabji

Cornelia Sorabji was the first woman to graduate from Bombay University in 1887, and then went on to fight tooth and nail for her right to education, not just in India but in Britain as well. Denied government scholarship to study in Britain, Sorabji was finally able to join Somerville College, Oxford University in 1889 thanks to a scholarship put together by leading British women like Florence Nightingale. On arrival, however, she was denied permission to study law because she was a woman. But thankfully, British academician Benjamin Jowett arranged the permission for her by 1890. Again, in 1892, the examiner from London refused to test a woman law student, and Jowett convinced the Oxford University’s Council to override this, making way for Sorabji’s final examinations and becoming not just the first woman, ever, to study law at Oxford, but also India’s first qualified woman lawyer. However, Sorabji wasn’t given her degree until 1922, when the law barring women from studying law was changed in Britain. Sorabji, on returning to India, had to campaign for 10 years to persuade anyone to employ her in law, despite her remarkable qualifications. Sorabji then decided to aid the purdahnasheen women in legal matters, and it’s believed that by the time of her death in 1954, she had helped over 600 women and children get legal rights to their property.