It’s no secret that India is a hub of handloom and textile crafts. While the past years may have led to a dip in demand for indigenous products, recent times have successfully turned the tide, leading us back to where we started. Indian textile crafts, however, are so much more than just that handloom sari you picked up or one that was passed down generations, it’s a major source of livelihood to artisans spread across the country. As per the fourth All India Handloom Census (2019-20), the numbers stood at 26, 73,891 handloom weavers and 8,48,621 allied workers, across states like Assam, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Chattisgarh, West Bengal and almost every state of the country.

As times change, so does the demand and so does the way Indian textiles are made, marketed and sold. This transformation of the Indian craft is evident in Varanasi-based brand Shanti Banaras’ journey. Coming from a family of four generations that have worked with Indian crafts in the wholesale market, Khushi Shah founded retail brand Shanti Banaras to bring light to the timeless craft of Banarasi Zari. “In our wholesale division, we were dealing only with normal silk and handwoven silk sarees. But then we also wanted to get into embroidery and real zari and for that, we opened Shanti,” she explains, “we had some people demanding for a retail store to showcase our talent.”

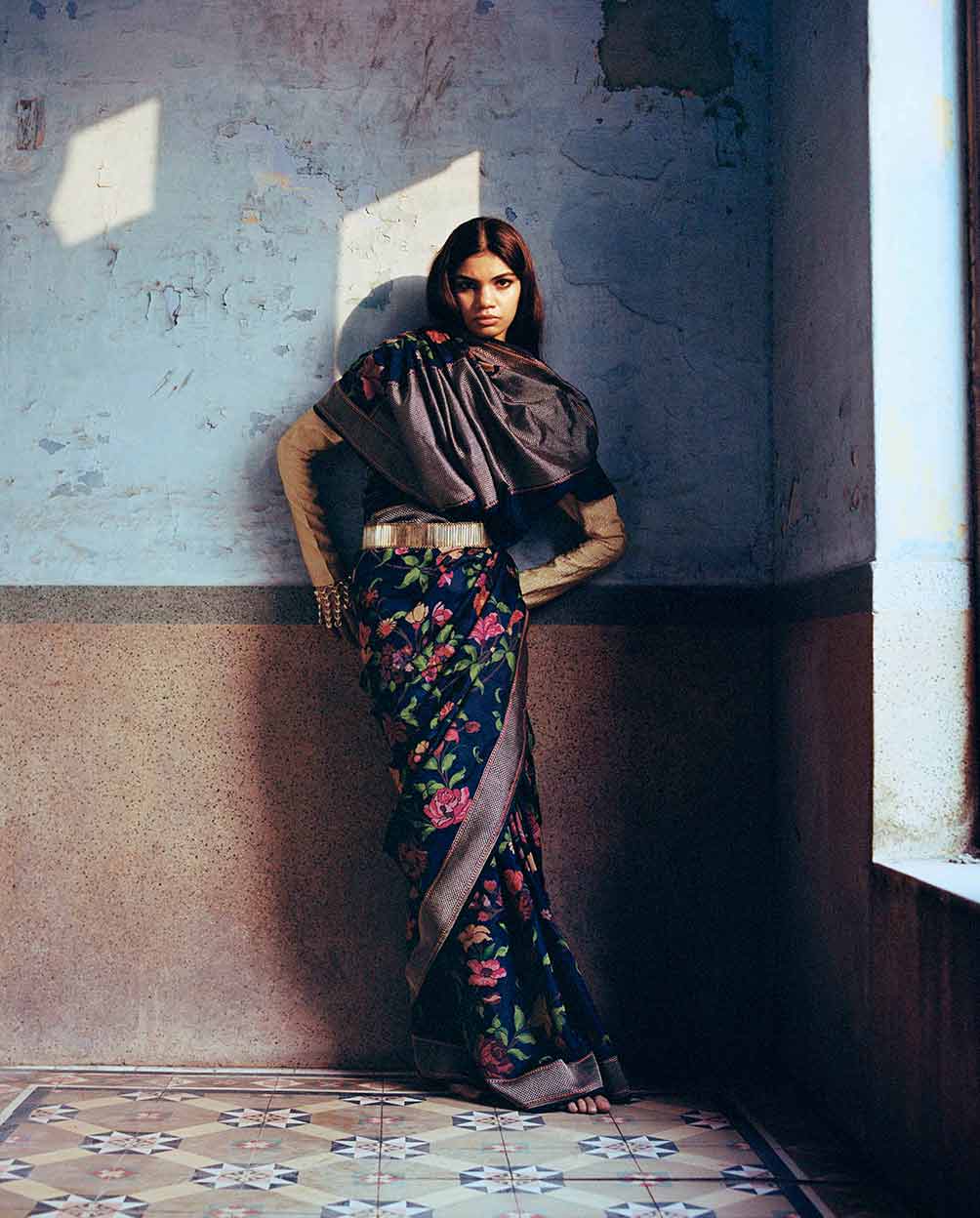

A speciality of the ancient city of Varanasi, the craft of Banarasi Zari dates back to the 19th century. Woven with real gold and silver, Banarasi Zari is almost like a piece of jewellery, Shah says. Shanti gives this traditional craft a more contemporary touch with unique motifs, transforming the craft into its new-age version. And transformed it has, the contemporary designs on each piece, right from stripes to modern Parisian-style motifs, Shanti’s brand ethos reflects beautifully through its creations. A version of the Indian textile that is much preferred by today’s Indian women, it is also a reflection of how the past few years have changed the craft of handwoven fabrics itself. While the craft and the fabric are still as cherished, it's mostly the silhouettes and styles that have evolved, pointing to how evergreen these fabrics prove to be.

Today’s consumer is also a lot more aware and eager to learn the nitty-gritty of the craft. “It’s interesting to see that they actually want to know the detail of what has gone into making a piece- how much manpower has gone into it,” Shah adds. Shanti’s saris come with a tag that mentions the percentage of silk and zari that has gone into making it.

With the sense of a revival phase underway, the craft has come a long way since it first surfaced. Once worn exclusively by nobles and royalty, Zari pieces are a part of family heirlooms passed on from one generation to the other. Shanti traces a small part of this phenomenon through its latest campaign, Samay. “We created a film that is reflecting back in time. It shows a woman looking back at earlier times where she was wearing the same sari that she’s wearing now,” says the founder. The campaign beautifully sets the tone of the quality of timelessness of pieces made with this craft.

The way it all started, however, for Shanti, is the story of most Indian households. “My grandmother would wear saris every day and she would be very particular about her drape and would look spectacular,” explains Shah, adding how her grandmother was the main source of inspiration for the brand, that is named after her. “She gifted one of her saris to my mother, who doesn’t wear saris that often and is more comfortable in suits. She got it upcycled and got a suit made out of it,” she adds.

But as women across the country rejoice at the “comeback” of handloom crafts, the same may not be true for Indian weavers. The huge community of craftspeople has been through a tough struggle in past years, starting from the 2016 demonetisation and now the slowdown due to the pandemic. The craft is usually passed down through generations of weavers, may not be taken up by younger generations, as is tradition. “I had a candid conversation with one of my weavers who told me how his son is not interested in getting into this industry because it seems like it’s slowly dying,” adds Shah, “The weaver community is huge, so it’s very important for people to even buy this to support the art because the work they’re doing so beautiful and intricate that no sort of power loom will be able to take over it.” The founder went on to explain how irrespective of circumstances, people who understand the art and handwork closely don’t make the switch to power looms that easily and continue to support the craft.

Shanti’s new store in Delhi’s Mehrauli was launched recently and houses a varied collection of embroidered lehengas, handmade artworks, and shawls apart from Banarasi Zari pieces.

Shanti's new store in Mehrauli, Delhi.