A humble fabric that went from an economic wardrobe choice to a sartorial symbol of India’s freedom struggle, Khadi has come a long way when it comes to evolving with the times. Literally speaking, the word Khadi is derived from the term ‘khaddar’, as the handspun fabric was called in the Indian subcontinent. Its roots can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, which left behind archaeological evidence, such as terracotta spindles for spinning, bone tools that are usually used for weaving and figurines wearing woven fabrics.

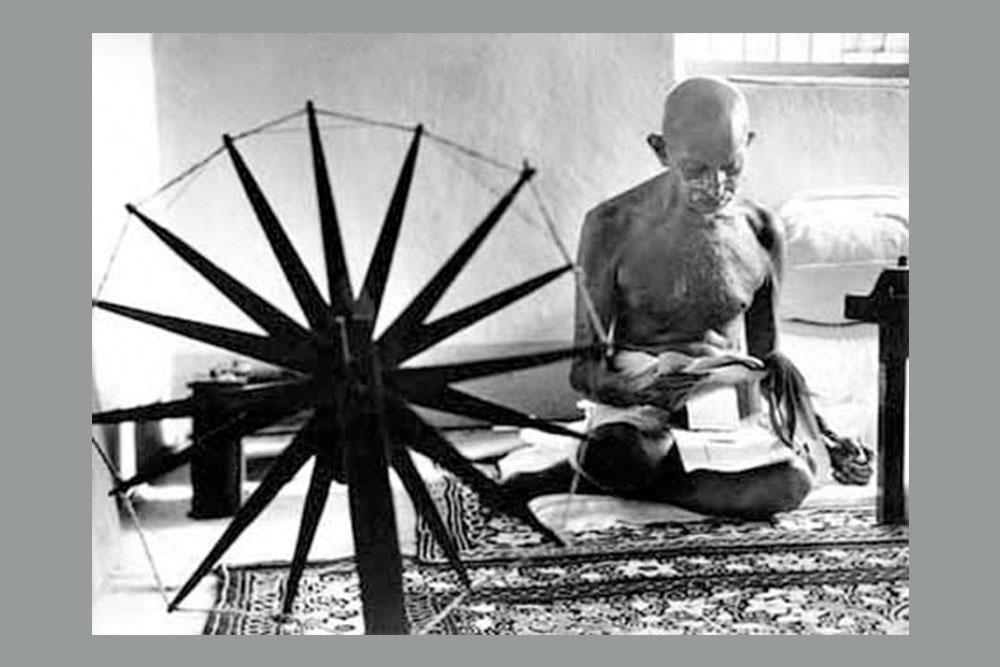

Image used for representational purposes only.

The Fabric That Freed The Nation

It was, however, during India’s independence struggle that Khadi really took the nation by storm. During the late 1600s and 1700s, the French and English brought with them a sea of low-cost fabrics manufactured in European mills. Additionally, Mumbai, or Bombay, as it was called back then, as well as Ahmedabad, saw the introduction of textile mills. This collectively resulted in a sharp decline in the demand for handcrafted fabrics like Khadi, leaving countless weavers across the country without a source of livelihood.

After years of struggle and an economic crisis, especially in the lives of the poor, one man decided that it was this handspun and handwoven fabric that could become the symbol of India’s freedom movement. That visionary was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who in 1918, started the Khadi movement in India. While it would still take close to 30 years for India to be free, these years were vital in the evolution that Khadi went through. The charkha, which is used to spin the yarn for Khadi, became an iconic symbol in the movement. Gandhi used Khadi to advocate the use of “swadeshi”, or domestically produced products, in an order to encourage a sense of self-reliance amongst the masses. He encouraged people to make their own fabric, along with other products, to help free Indians from mass poverty.

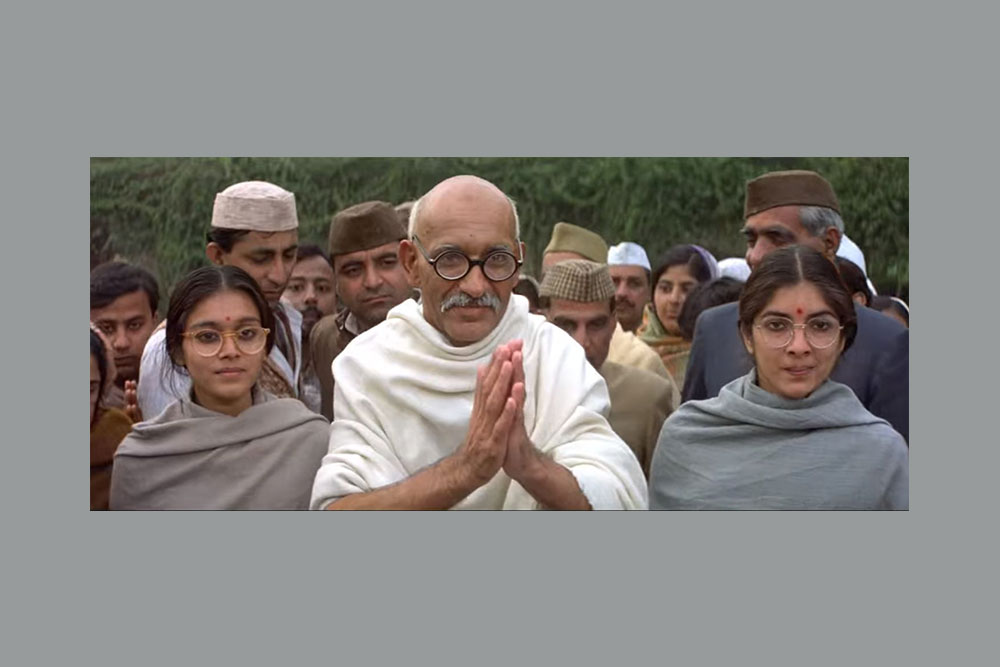

Image Source: Nationalheraldindia.com

In the aftermath of the Non-Cooperation movement in 1925, the All India Spinners Association was launched with the intention of propagation, production and the selling of Khadi. Members were required to propagate the charkha, wear khaddar, and spin 1000 yards of yarn per month. Through two decades, until independence, the organisation helped improve the production process and demand of Khadi in the country.

Khadi Gets A Facelift

It was after independence that the fabric was given a breath of fresh air. The All India Khadi and Village Industries Board, popularly known today as the Khadi, Village and Industries Commission (KVIC), was established by the Indian Government in 1957. It has since promoted, and developed the Khadi market, supporting weavers and other rural artisans.

Image used for representational purposes only.

Starting in the late 1980s, Khadi transformed from being the humble yet revolutionary fabric to one that was versatile and fashionable. It started with KVIC organising the first Khadi fashion show in Mumbai in 1989, showcasing more than 80 Khadi styles. This was followed by acclaimed designer Ritu Beri and her first Khadi collection which was unveiled at the Tree of Life show held at Delhi’s craft museum in 1990. Oscar-winning film costume designer, Bhanu Athaiya, famously dressed Richard Attenborough for the 1982 film, Gandhi, in Khadi clothing. She also used the handspun fabric for the 2001 period film, Lagaan, keeping things true to reality.

Image Source: Filmsufi.com

21st Century Khadi

The 21st century saw Khadi being used in different versions, different fabric blends as well as embellished luxe designs from designers like Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Ritu Kumar, Gaurang Shah and Anju Modi. More recently, Khadi has become even more popular with new age and homegrown brands that are using the versatile fabric in innovative ways. Sustainable brand, Desitude, uses Khadi denim for its customisable denim line. Brands like Eka, One Not Two, and Asa use Khadi for breathable and contemporary designs as well.

Image Source: Ogaan.com

The fabric itself has gone through quite a change as well. Inherently, it’s versatile enough to keep you cool in the summer and warm when the temperature drops—a feature that remains constant in most Khadi blends. The fabric that would once be treated with starch to get a stiffer shape, is now being used in its softer and more flowy avatar, more adaptable for easy silhouettes and designs.

Image used for representational purposes only.

As per KVIC, overall Khadi production, which was ₹ 879.98 crore in 2014-15, saw a growth of more than 100 per cent, reaching ₹ 1,902 crore in 2018-19, whereas, its sales recorded a growth of over 145 per cent. Not only that, KVIC created about 20 lakh new jobs just between 2014 and 2019. Today, the organisation that sells not only Khadi fabric and garments, but also beauty and lifestyle products, saw a rise in the number of sales even during the pandemic, growing from ₹840.97 crore in FY 2019-2020 to ₹3,079 crore in FY 2020-2021. As of the 2021 financial year, the number of Khadi institutions stands at 2,790, involving a whopping 4.97 lakh artisans.

Image used for representational purposes only.

While its reinvention continues, the fabric not only remains a favourite amongst designers and labels but still stays strong as a symbol of self-reliance and freedom, owing to its rich history, heritage and versatility.