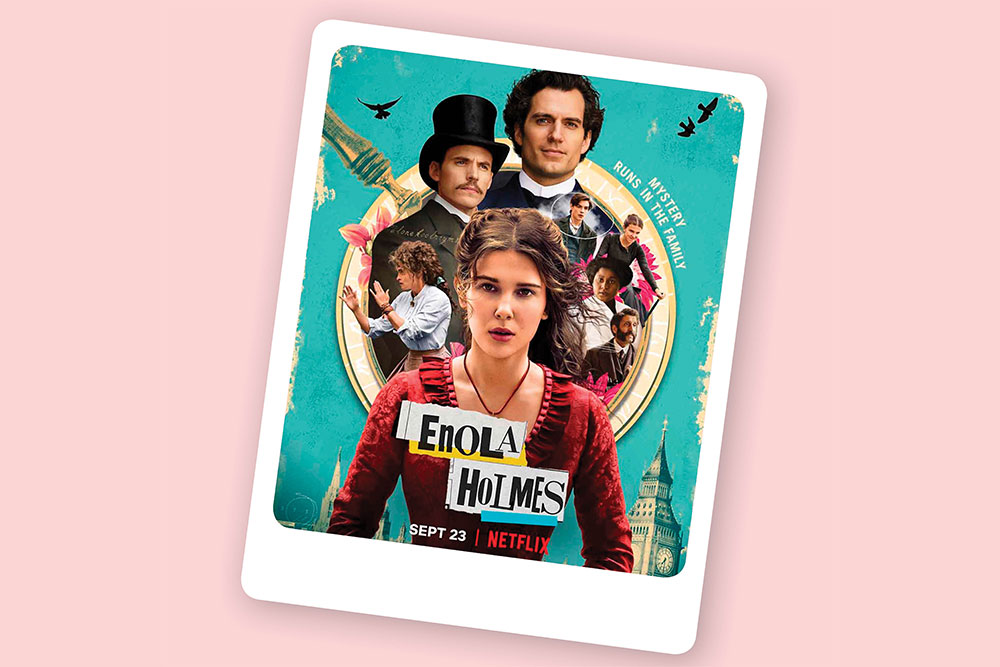

You’ve watched her portray the troubled Eleven in Netflix’s Stranger Things, and now you’ll see her in a whole new light. Millie Bobby Brown is called to essay the titular character of Netflix’s Enola Holmes—the 16-year-old sister of the acclaimed detective (yes, you guessed it—Sherlock), in a role that demands wisdom and skill beyond what an average teenage girl in that era is capable of possessing. What follows is a hunt for answers, and a storyline that’s ripe with murder and intrigue, set in an unforgiving Victorian London that’s dark and mean. The game is indeed afoot!

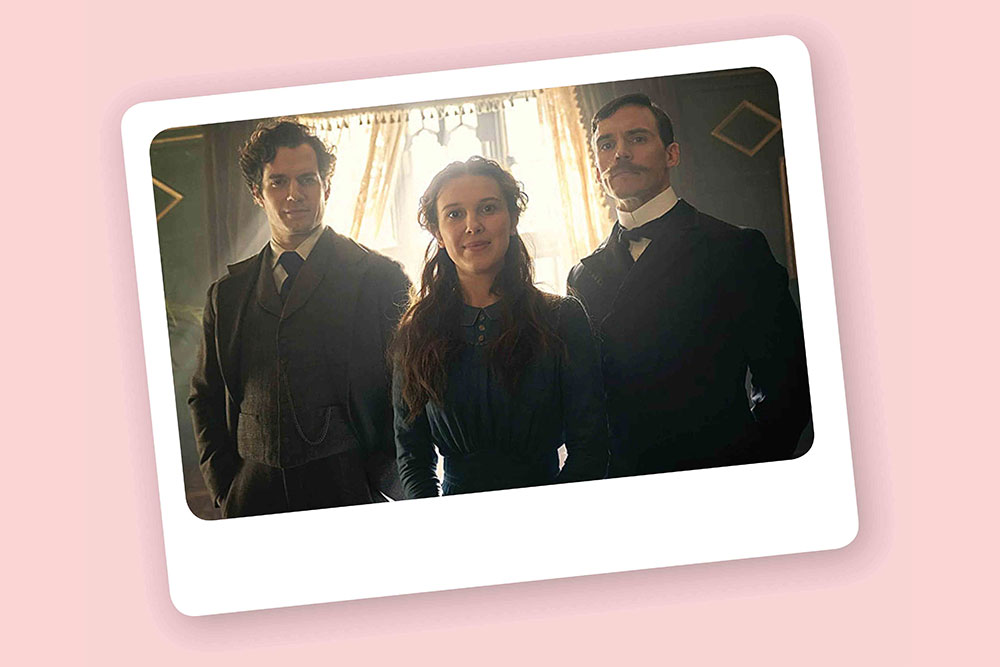

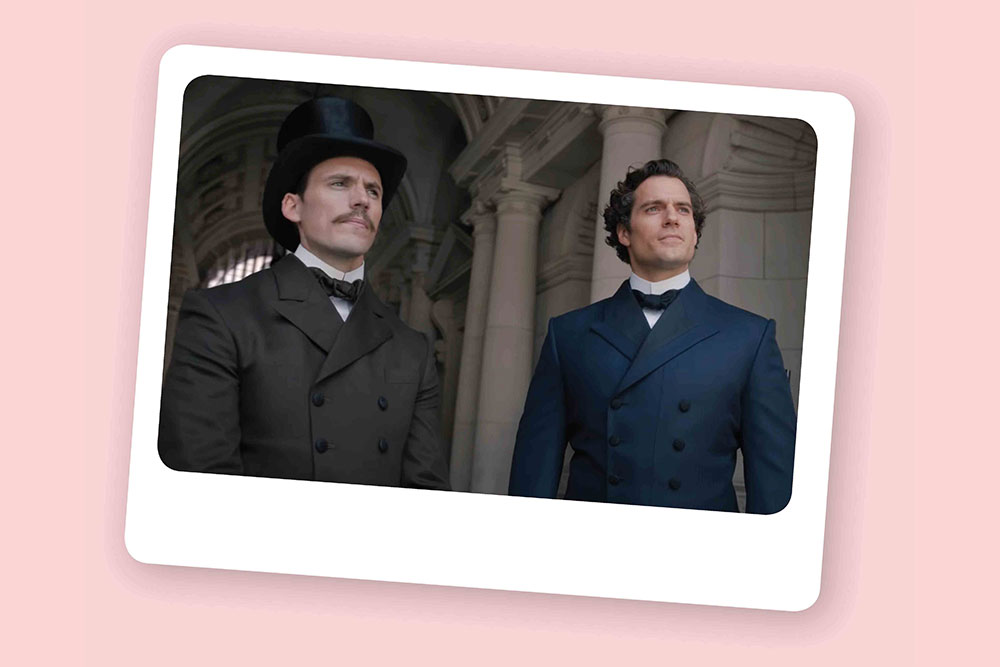

The film, based on the first book in the Enola Holmes young adult novel series by Nancy Springer (The Case of the Missing Marquees in which Enola is actually 14 years old), follows the adventures of Sherlock’s and Mycroft’s (portrayed by Henry Cavill and Sam Claflin, respectively) younger sister. Directed by Harry Bradbeer, it centres on the most uncharacteristic and unladylike teenage girl who would much prefer to shoot arrows and jump out of moving trains, than take a husband. This damsel may be in distress, but she doesn’t need a man to do the saving.

Fiercely independent (since it’s established from the beginning that Enola spelt backwards is Alone), the film is a coming of age, and a rather beautiful portrayal of a young woman taking matters into her own hands. In fact, you will hear her proclaim with utter conviction, “I don’t want a husband.” Naturally, this doesn’t sit well with her brother Mycroft who, as would any man in that time, expect her to act like a lady and conform to society’s patriarchal views. This is evident in his response, “And that is another thing that will have to be educated out of you.” Eventually, this is what comes to define the central conflict in the film—female liberation in a rigid patriarchal society that’s unwilling to evolve. And given that the young detective hasn’t really grown up with any male role models to “educate” her in these gender stereotypes, she’s blossomed with the ideologies of her forward-thinking mother, Eudora (essayed by dynamic Helena Bonham Carter), whose way of life is reflected in one anthem: “Our future is up to us.”

However, Mycroft isn’t the only chauvinist (again as was characteristic of the men at the time) depicted in the film. Sherlock may not have been as alarmed after meeting his baby sister, but was equally dismissive of her intellect, “Thoughtful and imaginative, perhaps, but certainly no stranger to the weakness, the irrationality, of her sex.” However, Cavill’s Sherlock becomes far more forgiving towards the end of the film when he decides to not underestimate his sister any longer, and takes her on as his ward.

The film delivers on multiple fronts, but two accounts stand out: first, Brown gives us a powerful performance and we can’t wait to watch how she takes thing up a notch in the next instalment; and two, the writers meant for Mycroft to be contemptable and hated, and Claflin managed that splendidly through his performance. What lacked, however, is the cunning and condescending smirk that’s become synonymous with the portrayal of Sherlock and his deductive prowess. Cavill, dimpled-chin et al, and a towering personality nonetheless, could have perhaps been better utilised throughout the film. Instead, he’s relegated to mere eye candy, not that we’re really complaining.

Ultimately, this 123 minute-long film, does make for a must-watch, especially given its takeaway—our future is up to us. And that’s a big positive in my book.