Women share a deep connection with nature—this might be a fact you’ve heard many a time, but do you know why this is so widely and globally believed across all cultures and ethnicities? This is primarily because both women and nature are sources of life, procreation and prosperity. Both women and nature are addressed as she/her because the very existence of planet Earth, and all life on it, depends on them. Humankind has attempted to preserve and celebrate both nature and womanhood through religion—especially the pagan ones that borrowed deeply from nature itself. Be it in Hinduism or ancient Greek or Chinese religions, the power of the feminine and the fertile superseded all others. We are, of course, familiar with how Hinduism celebrates the feminine power, whether it’s that of life and power through goddess Durga and Shakti, fertility through goddess Kamakhya, wealth through goddess Lakshmi, knowledge through goddess Saraswati, or death through goddess Kali. Now, if you’re wondering about how other ancient festivals from across world religions—especially those that are no longer practiced—celebrated the dual powers of nature and womanhood, read on.

Feminine Festivities In Ancient Greece

The ancient Greeks are credited for inventing a lot, and democracy (or at least a type of it) was one of them. Women, however, did not enjoy the right to vote, own property or inherit it, even though some of them enjoyed citizenhood of city-states like Athens. And yet, there were a number of ancient Greek festivals that were led by women. The three-day-long festival of Thesmophoria was celebrated in honour of the goddess Demeter of harvest, agriculture, fertility and plenty. Most rituals of the festival were carried out by torchlight, and by women, to promote the fertility of the lands and the women themselves. The festivals of Haloa and Skira also celebrated womanhood through the power of Demeter.

The festival of Aphrodisia was celebrated in honour of the goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite. Though celebrated by both men and women in ancient Greek towns like Attica, in some like Athens, this festival was especially celebrated by prostitutes. The power of Aphrodite was so immense over ancient Greece, that Athenian women celebrated Adonia to lament the death of the goddess’ lover, Adonis—that too in unofficial rituals that weren’t adhered to by men. This festival was celebrated by women across all social strata, whether they were prostitutes, citizens or non-citizens, who took to the streets and led huge processions on the day.

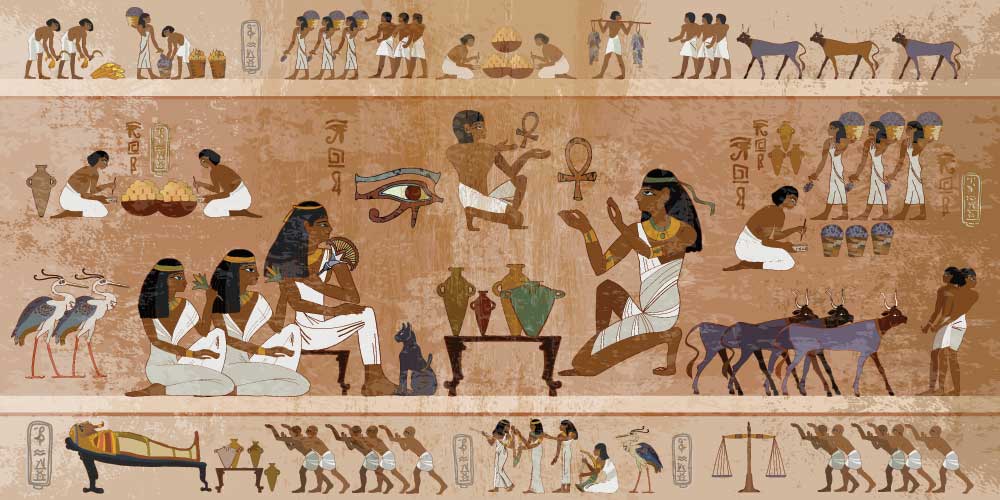

Ancient Egypt’s Feminine Deities

When it comes to ancient Egypt, we already have an inkling that this was a civilisation where women held immense power in their own right—at least through certain era, and in some roles—culminating in queens and leaders like Hatsheput, Nefertiti and Cleopatra. But did you know that the ancient Egyptians worshipped many goddesses who were linked to nature’s feminine power? Hathor, the sky goddess, was not only the feminine counterpart of Ra, the sun god, but also considered the mother of all pharaohs—thereby the source of their divinity and power. Hathor exemplified the Egyptian power of the feminine, and many festivities around the year celebrated her powers and blessings, especially in towns like Dendera and Thebes.

Another powerful female deity worshipped by the ancient Egyptians was Bast or Bastet, the goddess of women, home, domesticity, cats, fertility and childbirth. Considered to be the most elaborate festival in ancient Egypt, the festival of Bast freed women from all constraints. While the goddess Bast is no longer actively celebrated, the fact that popular fiction comic book characters like the Black Panther refer to her reveals the immense power she held over the people of the African continent.

How Ancient Rome Invoked The Feminine

Like their ancient Greek counterparts, ancient Roman women had citizenship rights, but could hold no right to property or wealth inheritance. And yet, when it came to celebrating the feminine power through festivals, the ancient Romans engaged in rituals with abandon and without any inhibitions. A prime example of this is Lupercalia, celebrated on February 15 (remember, the Romans gave us the modern calendar?), which is also thought to be a precursor of the modern Valentine’s Day. A pastoral festival that focussed on promoting health and fertility, Lupercalia was a day when Romans sacrificed animals, roamed around naked and coupled with random people. Men and women who became lovers on Lupercalia often went on to stay together for years, or even got married, to promote fertility.

But apart from Lupercalia, the primary festival Roman women celebrated was Quinquatria, dedicated to the goddess Minerva of wisdom, strategic warfare, justice, law, arts and trade. Celebrated on the Spring Equinox, this festival focused on the rebirth of nature and women, and was believed to be the beginning of auspicious times for women—which is why many took to consulting fortune-tellers and seers on this day. Similarly, Matronalia—celebrated on March 1, the first day of the Roman annual calendar—was dedicated to the goddess Juno, patron of childbirth. Women, especially mothers, received gifts and organised great feasts to celebrate this festival.